Home » 2013 (Page 2)

Yearly Archives: 2013

The Difference Between The Kanban Method and Scrum

A question that I often get while speaking with people is:

What is the difference between Kanban and Scrum?

I know this topic has been explored at length in many places on the internet and also with a variety of different answers, but I’m going to put my thoughts down and share them with you because:

- I still feel there is a lot of misunderstanding on this topic and I think I have something to add to the conversation

- People still ask. The more of us who can blog and promote conversation on the topic, the better.

- Getting my thoughts out and in a more concrete form that I can reference (and send people to reference) should promote better conversations as well.

So. Here it is. Kanban Method. Scrum. I imagine I’m about to step on some toes but I hope we can have some good debates and not conversations filled up with rhetoric.

Similarities

Goals

At their hearts, both methodologies are attempting to do the same thing. They are attempting to advance the state of the art in work management predominately (but not only) in the area of knowledge work.

Value-system Influences

Both are heavily influenced by value-systems. Scrum is primarily influenced by the Agile Manifesto which describes the “Agile” value system. The Kanban Method pulls a great deal of its values from a Lean value system. There isn’t really a “Lean Manifesto” but the works of Taiichi Ono and W. Edward Deming contribute to a common understanding of what it means to be a lean thinker. They are not the only contributors but have made the most significant impressions on the Lean/Kanban community. The Kanban Method is also influenced by the Agile Manifesto and the values inherent within it.

Increments

Both methodologies believe in delivering software incrementally to maximize the opportunity to get feedback and capture ROI. Incremental delivery of software also mitigates risk and maximizes the opportunity to learn from a business, process, and technical perspective.

People-centric

Both methodologies are striving to make people a central aspect of the system, which they should be. 😀 Scrum strives to “protect” the development team from the influences of “traditional” project management tactics. Kanban suggests that we need to allow solutions to problems emerge from the people in the system. Kanban also believes that changes should not be forced on people, but that people need to own the changes and be supported throughout the transition. Both systems try to give people the time and space required to improve.

Similarities with Significant Differences

Learning

Both approaches promote an intent to learn and improve. In Scrum this is primarily achieved through the retrospective tactic which is an Inspect and Adapt-based tactic. The team will get together (frequently) to discuss processes and tactics that have been going well and should be continued, things that haven’t gone well and should be changed for the next sprint. I do not believe that Scrum teams put sufficient emphasis on this aspect of Scrum and that the common understanding of Scrum doesn’t promote this aspect strongly enough. I also believe that the scope of the area under review primarily focused on the team. Again, this may not be the intent but it is, in my experience, the way it is implemented.

The Kanban Method has learning at the core of the methodology. There are several reasons for this, but the primary reasons for this are:

- Do nothing without understanding the current situation

- The current situation is always changing

- New challenges (technical and business) are always arising

- People, who are at the heart of the system, need to be learning constantly in order to be improving themselves and the system continuously

- Without a learning approach to improvement, you can’t use experiments to test improvements

The Kanban Method uses more of a Plan – Do – Study – Adapt (PDSA) approach to learning and this is different from a Inspect and Adapt approach.

Cadences

Scrum prescribes a cadence and that all activities happen within that timebox. If you didn’t guess, this cadence is called the sprint duration. Sprint is just another name for the resulting timebox.

The typical Scrum cadence now a days seems to be 14 days (2 weeks) and follows the following sequence of:

Sprint Planning -> Execution (daily Scrum meetings) -> Iteration Review -> Retrospective -> repeat cycle

Scrum’s Sprint duration is a great innovation over the traditional approach to managing work. Because the guidance on duration has never been longer than 30 days, Scrum teams have always been guided to strive for shorter feedback cycles than traditional projects. Scrum teams have also been guided to produce increments of software at the same rate. In order for Scrum teams to do this, work has to be decomposed and understood by the development teams. Work gets prioritized more frequently and this prioritization allows these teams to be agile from a business perspective. Risk can also be explored and mitigated within the sprint and that knowledge feeds back into the prioritization loops of the team.

In the Kanban Method, cadences are just as important as they are in Scrum. Many Kanban teams have a Queue replenishment cadences. This is effectively the same as the Sprint Planning activity in Scrum. Many (most?) Kanban teams have a daily stand-up meeting where the team discusses the current state of the kanban system, looking to remove impediments and manage work at risk of taking longer to deliver than expected. Many Kanban teams will have product demos (iteration review) that coincide with an opportunity to deliver or deploy the product being built. And many Kanban teams will have Operations Reviews which are an opportunity to discuss the Kanban teams progress and improvements with the rest of the organization.

The significant difference between the two systems is Kanban does not typically use timeboxes and all of the cadences in a kanban system can happen when it is best for the organization to do them.

Timeboxes are a mechanic that Scrum uses to minimize disruption to the development team. In Scrum, changes to the Sprint plan are strongly discouraged. Plan the two weeks, then let the team work uninterrupted. This has allowed for great improvements in productivity in software development, but what if we could apply that protective attitude to a single piece of work. So while a team was working on an item, they were not disrupted but they could be counted on to pull the next highest priority item on the queue as soon as they were ready to pull some work. The business could prioritize as much as needed while the team had work in progress.

Timeboxes are also used to provide a consistent interval that external parties can interact with the Scrum team. Business can plan around a 2 week cadence to injecting new requirements into the system, and downstream partners (IT, Sales) can count on getting new work or increments of software every 2 weeks as well.

In Kanban, the cadences that are most appropriate for the external partners can be allowed to emerge and do not need to be enforced (or tied together) by the development team. There are advantages for shorter cadences, but what if we could get all the way down to Just In Time and we no longer had cadences on replenishment and delivery? We can still have cadences on Ops Reviews or any other ritual that benefits from these cadences. What if replenishment happened every week, or daily, and delivery happened every 4 weeks? Or on the 25th day of each month? That is an advantage that many organizations benefit from when adopting a kanban system as a way to manage work.

Pull-based , WIP Limiting Systems

Both Scrum and Kanban ARE Pull-based, WIP Limiting systems. Scrum uses, in many senses, a kanban system at the heart of how they manage work. The Scrum team PULLS only the work they can manage into the iteration. The iteration planned work is the maximum amount of Work In Progress (WIP) that the Scrum team will be expected to deal with. The limit of the amount of work in the iteration is set by the team’s previous velocity measurements. But then we will start to encounter the limitations of the Scrum work management system. Scrum teams can still start a lot of work and suffer from the inefficiencies of multi-tasking. Having a lot of work in progress (started) but not finished is a significant source of waste in our industry. Humans cannot multi-task, we context switch and we all know that context-switching is expensive. Scrum does not have specific guidance to limit multi-tasking within a team. (Note: Please correct me if I’m wrong here. Haven’t read the Scrum Guide recently)

In a Kanban Method implementation, the focus is to limit WIP at a more granular level. Preferably at the work item level but we can also let the most appropriate granularity emerge by leveraging the learning aspects of the method. We use WIP limits to guide our intent to finish work before we start more work. We also use WIP limits to reduce overburdening. WIP limits are a great way to fine-tune your Kanban system and how and what to set them to would require a lot of explanation. Suffice to say that Kanban’s WIP limiting tactics allow for significantly more tuning that Scrum’s Sprint Planning tactic.

Work Items

Scrum teams tend to categorize work into two types, User Stories and Bugs. Both can be decomposed into tasks. Scrum actually provides guidance that there are “product backlog items” and that User Stories and Bugs may be types within that backlog. Additionally, Scrum allows work items to be of the same type but vary in size. This size is often described in Story Points. So one User Story may be 3 points, another may be 13 points. And there is no common interpretation of a point between different Scrum teams. What a story point actually means is specific to a Scrum team.

Kanban Method teams tend to have numerous types of work. Requirements, User Stories, Use Cases, Bugs, Defects, Improvement Activities are all examples of work items I’ve seen on Kanban boards. Whatever makes the most sense for the organization. Kanban differs from Scrum in that it generally does not try to categorize work by a size. The size of the work items in a Kanban system don’t really matter from a management and monitoring perspective. Once the item has been committed to by the Kanban team, they should finish it within the expected timeframe given how big they think it is when starting. It is when it starts to exceed expectations that the Kanban team should start to pay closer attention to it and take corrective actions if possible. But other than setting an expectation when the work is committed to, sizing isn’t important from a work management point of view. It should be noted though that smaller work items are usually easy to manage from a development point of view because the larger a work item is, the more likely that item is to contain significant unknowns and lots of uncertainty.

Metrics

Both Scrum and Kanban use metrics to help drive behaviour and decision making.

There is really only one metric in Scrum. Velocity. Teams will assign a estimated value to a work item that is used to indicated how “big” it is. The team will work as many items as they can in a sprint. Once the sprint is completed, the values of all completed work items will be summed up and that was the teams velocity for the sprint. This velocity will be used to determine how much work is pulled into the next sprint during sprint planning. You can create burn-down or burn-up charts based on the velocity metric as well. Typically, this is as scientific as a Scrum team will get. The summing of a subjective measure of size on a work item.

In The Kanban Method, all measurements are intended to be quantitative. Something that is measured and the value is (usually) not really debatable. In Kanban, we tend to measure time (lead/cycle) and quantities of things (work items) at various points in the workflow. These are all concrete, measurable attributes of work in the system. All that is needed is start and end-points and you can now start the clock when work gets into a state and then leaves the state. This can be as simple as started and finished or much more complicated with numerous states and parallel activities steams within a workflow. We also measure how many of something are in a particular state as well at a time as well. Ultimately in Kanban, we measure how long it took something to get somewhere. With these measures, we can determine rates, quantities, and speeds of work items and establish a deeper and more meaningful understanding of the system.

Differences

Workflow

Generally speaking, Scrum prescribes a set of activities that are performed within a Sprint. There is not any guidance on particular daily development activities but generally you should be analyzing, developing, testing, user acceptance testing throughout each day as applicable. But most Scrum teams will always do Sprint Planning, Development for the rest of the sprint, Iteration Review and Retrospective.

The Kanban Method does not prescribe any workflow. The workflow that you model in your Kanban system should be YOUR WORKFLOW, and it should evolve as required based on things that are observed and needed by the organization. A kanban system is expected to evolve and change over time as the organization (and it’s needs) change over time.

This also includes cadences. Scrum generally prescribes that the workflow happens within a cadence. Kanban does not prescribe cadences. It does appreciate the value of cadences but feels they should emerge where needed and the interval should be as long as needed, but Just-In-Time as much as possible.

Roles

Kanban does not prescribe any roles. Roles and responsibilities (and changes in them) should emerge based on the organizational maturity and understanding of the development process.

Scrum generally prescribes three roles, Scrum Master, Product Owner, and Team Member. If you’re on a Scrum team, you’re normally categorized as one of these things. I think that this can be a good thing, but it can also backfire as people try to find their place on the team. The individual esteem system of a person is influenced by what they think their place in the world is. Changing that place in the world can shake a person’s esteem and confidence, which tends to diminish their acceptance of a system or change.

System Thinking

Most people’s interpretation of Scrum is team-centric. This isn’t a necessarily a bad thing, but at some point it may become a limiting way of thinking when trying to scale Scrum or work with upstream and downstream partners of the Scrum team.

The Kanban Method takes a system thinking approach to process problems and expects the impact of changes to ripple throughout the entire workflow of the organization as business need/idea goes from inception (idea) to realization (software). Generally speaking, the kanban system is intended to protect the “work” (and therefore the team) from being disrupted so we don’t have to have a team-centric view of things. We can take a system thinking view of things and understand that every interface to our “team” system is actually an interface with a larger system that could benefit from The Kanban Method implementation.

Final Thoughts

This post has been much longer than I expected and I’m not sure I’m even done, but I think I’ve covered off what I think are the similarities and difference between Scrum and Kanban.

What I want to leave you with though is that neither approach is wrong, nor do they need to be exclusive of each other. There are teams that have started with Scrum and arrived at a Kanban Method implementation, and there are Kanban Method teams that have arrived at a very Scrum like (or Scrum exactly) implementation because that set of tactics and tools were the best way to manage work for that organization. It should never be a Scrum vs. Kanban conversation, but rather a question of what is the best from both methodologies that I could use.

I believe there are aspects of The Kanban Method that Scrum doesn’t adequately address in our quest to better manage knowledge work workflows, so I do think that while you can always have a system with “No Scrum”, you should never have a system with “No Kanban Method” in it.

Thanks for following along on this rather epic article. I hope to hear from you, both positive and negative comments are welcomed.

A Rant about Estimation – When Will We Stop Being Crazy

Warning: This is a bit of a rant. If at any point in this post, I seem like the crazy one, please tell me somehow. Comments, Twitter, LinkedIn. It would be really valuable to hear your thoughts. But I also encourage you to think about the situation, context and information I provided and decide for yourself whether the way we are acting is crazy. There are craziness checkpoints along the way! And if you think any of this is crazy as well, try to do something about it!

I had a work colleague recently ask a question on our internal mailing list. A summary of the question would be:

A company that is using ‘agile’ wants to know if their formula for converting story points into hours is sound because executives are doing short term (< 6 months) planning.

This is an example of how they break down their work. Seems reasonable and just like many other companies.

They also provided a formula. This is where the craziness starts which is startlingly common in our industry.

… and a sample of how the formula works.

Ok. At this point, all that is going through my head is “OMG”. Now comes the process by which they populate the formula.

- PMs provide the Epic Point estimate

- Developers decompose epics and provide point estimates for the user stories.

- Teams points (epic points or user story points?) per resource per sprint are tracked.

This is COMMON in my experience working with many organizations in our industry.

In all fairness to my colleague, he knows this is crazy. The developers in this organization know this is crazy. This is a typical scenario when executives and senior managers are trying to get information but using techniques that we have proven don’t work in our industry.

The good thing is, the way that they decompose work is fine and the formula will work as long as we don’t have have 0 velocity or 0 team members. ![]()

The existence of the formula and the process by which we find numbers to put into it are where the craziness begins. First, a bit of information on “story points”.

Dave’s Craziness Meter

Story points are an abstraction agile teams use to REDUCE the perception of accuracy. 1 story point will require “some small” bit of effort to complete. 2 story points should require about twice as much effort as 1 story point. So that would be 2 times “some small bit of effort”. 5 story points require about 5 times “some small bit of effort”. I hope I’m clear about how we are purposefully reducing the perception of accuracy. Why? Because it incredibly difficult (usually impossible) and time consuming to create accurate estimates for the effort required to do knowledge work using the time units desired by decision makers!

I don’t even advocate using story points to my teams anymore. As numbers, it is too easy for people to plug them into a formula to convert them into something they are not intended to be converted into. I now generally only advocate sorting work by sizes like Small, Medium and Large.

Now let’s discuss the numbers that go into the formula from the example.

To start, a PM will make an point estimate in story points. In the example, it is 200 story points. I don’t know why a PM is doing an estimate on technical work.

Point estimates are bad. They imply accuracy where it normally does not exist. We have a point estimate of an abstraction that is trying to reduce the perception of accuracy. At least it is a single point estimate using an abstraction, so it could be OK except humans are optimistic estimators. Our interpretation of an estimate usually means that we expect the epic to fall in the middle of a normal distribution of epics and we have a 50/50 chance of falling under either side of the curve.

The problem with this is that the magnitude and likelihood of doing better than our estimate is the same as the likelihood and magnitude of doing worse than our estimate. And the other problem with this approach is it’s wrong. Using information from industry observations, we see that plotting the actual effort of our epics will form a log-normal distribution .

On a log normal distribution, the chance of doing better than our estimate is smaller than the chance of doing worse than our estimate. This means our epics usually fall behind the mode which means that they took more effort to complete than we expected. Simply put, when humans provide point estimates, we are usually wrong.

Let me state that again. When we estimate in knowledge work, we are usually wrong! And the formula above actually understands that!! The historical team buffer is a built-in admission that we need to add 20% to our estimates to make the numbers get closer to the actual values we observe!!! And I’ll bet that most epic actual values exceed the padded estimate!

Dave’s Craziness Meter

Ok, so point estimates are bad. And humans are bad estimators. That all came from the first point of the PM creating an epic point estimate. The rest should go more quickly. We’ve covered a lot of ground in that first exploration of the situation.

Next we have the developers decomposing the epics into stories and providing point estimates on those stories. All of the problems that we encountered in estimating above apply at this level as well.

The problem now is that it doesn’t work to simply sum up the points for the stories to get the points for the epic. If we look at the problems with point estimates, imagine doing that 20-100 times and adding the value together. We know that our our estimates are wrong (by at least 20% and probably more) and the impact of how wrong you are has a significant impact on effort. The only way to potentially add up the stories to see how much the epic will be is to estimate stories with an expected value that is the mean on a log-normal distribution and run a Monte Carlo simulation using all the stories in the epic. (That is an whole other blog post!)

I’m betting that a Monte Carlo simulation isn’t being used to turn the developer’s stories estimates into a meaningful epic estimate. Never mind the observed expansion (dark matter as David Anderson refers to it) of requirements that we see as we build the software and discover what we’ve missed. It’s always there, we just needed to build the system so that we could find it.

So our estimate is probably wrong. Significantly wrong. Period. Let’s move forward.

The next part of the formula is:

and the data in our example looks like this:

10 points is the average points per resource (I hate that word) per sprint. I’m assuming that they have standardized sprints for all teams in the organization. 2 is the number of team members (much better description) that will be working on this epic.

Do all developers produce 10 points per sprint, regardless of the task? Regardless of the skill level? Are we talking senior or junior developers? Is the business problem something they’ve done before, or something novel? Technology is know or new? Stat holidays? What if a developer is sick?

That 10pts could also be interpreted as developer velocity, and as we know, velocity can be highly variable for a team and is even more variable for individuals. In Scrum, we always talk about team velocity because it hides the variability of individual velocities that we know exists by averaging out the effort expenditure across multiple people over time. And we also know that velocity cannot be compared between teams! One team might have a velocity of 10 while another may have a velocity of 20, but the former team is more effective. The velocity number itself should not be interpreted as a standardized representation of effort that can be applied to any large scale planning activity (multiple project, multiple teams). It only works when you know the project and you know the team and it’s capabilities and past delivery history in specific contexts.

Dave’s Craziness Meter

So we have an epic estimate (crazy) divided by a developer velocity # multiplied by the number of team members (crazy). The next step is to multiply by the Historical Team Buffer otherwise known as padding the whole estimate.

The number from the formula is 1.2 in order to make the whole estimate 20% larger or 120% of the original estimate.

As I mentioned above, this buffer is a built-in indication that our estimates are wrong! We know we can’t deliver the epics as expected given our estimations, so we pad the estimate to make it closer to what we actually expect to do.

Dave’s Craziness Meter

So after all of that, we’ve arrived at a value of 12 sprints required to deliver this epic.

Phew!! Now we need to turn this into an expectation of effort expenditure or schedule.

Oddly enough, based on the question from our internal mailing list, we were not able to determine what the executives wanted. They either want to know how long it will take or how much it will cost. Unfortunately, I’d guess that they expect to get both from that number. They expect that the project will be done in 960 hours of developer effort which will occur in 12 weeks of calendar time.

That is 12 sprints and 80 hours of effort per sprint. That seems to be 2 developers for 40 hours per week or 80 hours per week.

So, I can with a fair bit of confidence tell you that the work week is 40 hours, 2 man weeks is 80 hours, and if a sprint is 1 week long with 2 people, the project will spend 960 hours of effort in 12 weeks.

What I can’t tell you is if both developers will work 40 effective hours per week. You almost certainly will pay them 40 hours per week, but whether all of that effort is applied to the story is another question. Emails, meetings, slow days, coffee cooler conversations, code reviews, design sessions, non-project related tasks are just some of the kinds of things that eat into that 40 hour work week. Never mind sickness or other work absences. Most people I speak with use 6 hours as a number for planning how much time a developer can effectively spend on a story. I’ve seen organizations where a team member regularly, for a variety of necessary reasons, spends less than 2 hours per day on a project they are supposed to be full time on.

So that does two things to our calculation. We’ve determined that the story is now about 960 hours in effort. If the developer can’t work on it 80 hours per week, the number of iterations has to go up! If the developers are only effective 4 hours per day, that means we have to spend 24 iterations on the project to get it done. Or potentially, the developers can deliver it in 12 weeks, but have to work 40 hours of overtime per week, which means the costs go WAY up for the project as the organization has to pay overtime. Let’s not even try to incorporate the diminishing returns on overtime hours, especially in an environment where that overburdening is chronic.

So as an executive, I wanted a fairly certain number for how much effort a specific epic is going to take so that I can do appropriate planning for the next 6 months. And 960 hours and 12 weeks calendar time is something I’m going to hang my hat on. I mean, 960 is a pretty precise number, and the “confidence” that the process has given the organization in that number must be pretty good.

Dave’s Craziness Meter

And since we’re doing organizational planning and planning multiple epics for multiple teams in the six month period, I’m also making the assumption that all epics that are 200 points are the same. And I’m assuming that all story points are the same effort. I’d have to deduce that that any epic of 100 points would take exactly half as much effort or half as much time as any 200 point epic. Any 200 point epic is exactly the same as any other 200 point epic. There is a lot of confidence in our formula and approach.

Dave’s Craziness Meter

Ok. I’ve maxed out my craziness at this whole endeavor. My hope is that you think this is all a little crazy as well because if we start to accept that we’re acting a little crazy we can start to do something about it.

Final Thoughts

I’d like to clarify that this post is not intended to be critical of people who are using Agile estimation techniques and trying to fit inside of an organizational traditional project planning methodology. We are all trying to do the best that we can. But sometimes we get stuck in a way of thinking. I’m hoping that this blog post might just jolt some of you into thinking about these problems and deciding to try and do something about them.

The formula used is as an example in this post is just that. A formula. And a very common kind of formula as well. The values you input into the formula will work as long as you don’t have 0 velocity or 0 team members. (No one likes division by 0.) In Kanban we use a lot of formulas and a scientific approach to understanding our work and workflows.

It’s the drivers underlying how we want to use formulas that we really need to be critical of. The formulas and the data that we feed into them has to make sense and drive us towards creating valuable data points on which meaningful decisions can be made. If we use complicated formulas and suspect or fictitious data as parameters, that makes the output worse than garbage because it provides some sort of sense of accuracy and a false sense of confidence because we think “this must be right. Our formula is sound.”

As long as we, as an industry, support this behavior, we’re are contributing to the continuation of this problem.

There are solutions to this problem, but exploring those options will be explored in another blog post.

But in the mean time, I’d love to hear your feedback! Do you think I’m crazy or do you think our industry is crazy?

Intro to Kanban at the Calgary .NET User Group’s Lunch Series

I recently had the privilege to speak that the Calgary .NET User Group’s new lunchtime series. This series is an opportunity for people to come and hear about exciting new topics with a minimal time commitment. And in this case, CNUG President Dave Paquette felt is was about time that we have a talk about Kanban.

Here is a link to the video of my 50+ minute presentation. It’s the first time they’ve video taped one of these, so please don’t be to critical of the quality. 😀

You can find the slides on Slideshare here.

The one thing I’d like to pull out specifically from this presentation was the exercise we went through (11:24 in the video) in understanding what it was we were actually talking about. In my slide deck, I indicated there are three common definitions of kanban out there and that we really needed to understand which one we were talking about in any conversation around the topic. And in an informal little survey of what participants though kanban was, we got the all three definitions from different people in the audience. The three commonly confused definitions are:

- kanban – signboard, visual signal, card

- kanban system – pull-based work(flow) management system, normally at the heart of a kanban method implementation

- Kanban method – An approach to incremental, evolutionary process change for organizations

Very often when I am discussing the Kanban Method with people who are new to any of these ideas, they are often getting them confused and it is really important that we clarify which we are talking about.

Do you know what Kanban you’re talking about? 😀

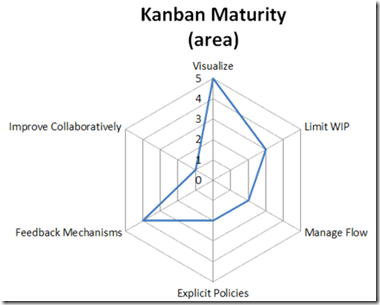

Kanban Maturity and A Technique for Visualizing It

I received a great question from one of my webinar attendees and this question has also received a bunch of attention from the Kanban community since this visualization first surfaced in the summer of 2012 ago at the Kanban Leadership Retreat in Austria.

How do we measure our maturity using the Kanban method?

I have used the technique that came out of Mayrhofen at #KLRAT as the basis for how I work with teams to monitor Kanban maturity. There isn’t a “standard” set of questions that the Kanban community uses in the creation of the kiveat chart. In general, it is being suggested that each team/coach comes up with a context-specific way of measuring and ranking maturity within the 6 practice groups that applies to “that team”. That visualization can then be used to monitor the anticipated growth for that team over the course of time. One thing that the Kanban community is cautious about though is “comparisons” between kiveat charts and assessments. Since each assessment is relatively subjective, comparisons should be avoided as it would be hard to compare and may potentially be misleading to the team.

That said, here is how I use the chart.

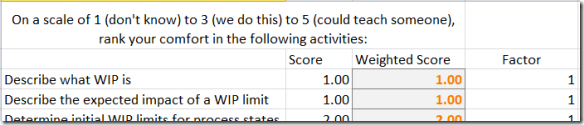

I have a set of questions I ask per category. On a scale of 1 to 5, 1 being “We do not do that”, 3 being “We do that”, 5 being “We could teach someone to do that”, I look for activities that would allow me to select one of those values for one of my questions. As an example:

Question: Identifying types of work

Observation: Does the team identify different types of work? Do they have User Stories, Bugs, Improvement Tasks, etc. described within their process? If they do not, they would be a 1. If they do, they would be a 3. I’d then look for evidence that they are capable of teaching work item type defining to another team, or that they could do so if required. If they could, they would be a 5.

I go through all of my questions for an axis of the chart and give them these rankings. I then take the average value of all of the answers and that is my data point on the kiveat chart. My visualization category currently has 10 questions in it, so if I get 35 total points/10 questions, I get a 3.5 visualization score on the kiveat chart.

My Limit WIP category currently has 5 questions, so 15 points/5 questions would give me a 3 Limit WIP ranking on the chart.

Following this pattern, I eventually end up with 6 axis on the kiveat chart, all ranked from 1 to 5 and this “coverage” can be used to describe the team’s Kanban maturity from my perspective.

David Anderson, in some of the slides I’ve seen him use and in talking to him, describes a progression of novice to experienced tactics within each category and each of his axis has different scales to represent the increasing maturity on that scale. He does arrive at the same kind of coverage visual and describes that coverage as an indicator of maturity from his perspective. My kiveat chart and David’s would not be comparable though and this is completely OK and encouraged. As I mentioned above, the current thoughts within the Kanban community are to discourage direct comparisons between these kiveat charts.

What kinds of questions would you use to measure you’re companies Kanban maturity?

What Should My WIP Limit Be? Super Easy Method to Find Out!

If you’ve built a kanban system, or you’ve tried to put a WIP (work in progress) limit on a phase in your workflow, you’ve probably asked or been asked this question. And very often, then answer is “I don’t know. How about we try n.” where n is a guess. Usually an educated guess like:

- 2 x the number of developers

- 1.5 x the number of people on the team

- Number of people involved + 1

And these are all ok places to start if you have no data, but with a little data, we can stop guessing and set our WIP limits with some empirical information and at the same time start building a system that will satisfy one of the assumptions required for us to use Little’s Law properly. There are two things that we need to have in order to use this super easy method:

- Data about average time in state for work items

- CFD (cumulative flow diagram)

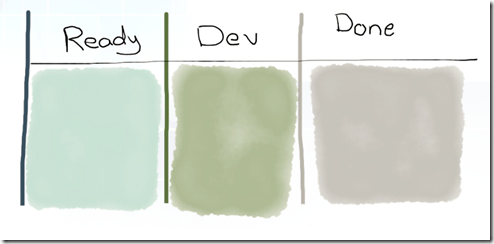

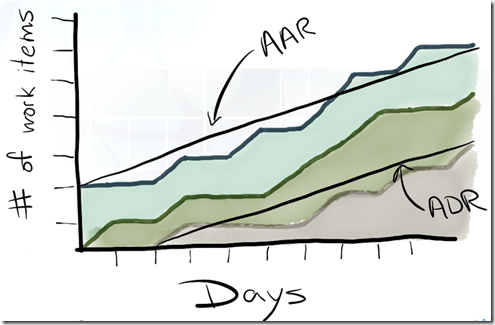

Ok, I guess we don’t need the CFD if we have the data, but it sure is nice to visualize this information. 😉 We do need to have some data about the way that work passes through our system and we need the data that would be required to create a CFD. For the purposes of this post, lets assume that we are capture the time in state for each work item. Entire time in the system is often called lead time. Time in between any two phases in the system can be cycle time but we’re interested in cycle times for a single state at a time as our objective is to determine the WIP limits for each column in our kanban system.

Let’s use a simple approach to measuring average time in state in days. On our simple kanban system above, we have a Ready State, Development state and a Done state. Each day, we count the # of items that have cross a state boundary and put those numbers on our CFD chart. After several weeks, we have enough data to start calculating a couple new metrics from our CFD.

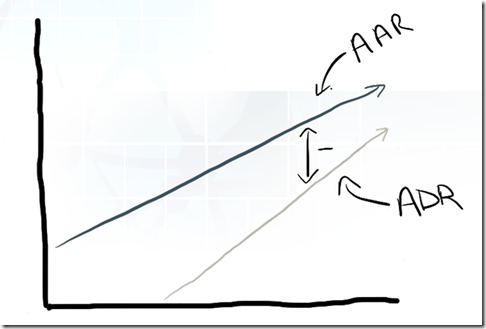

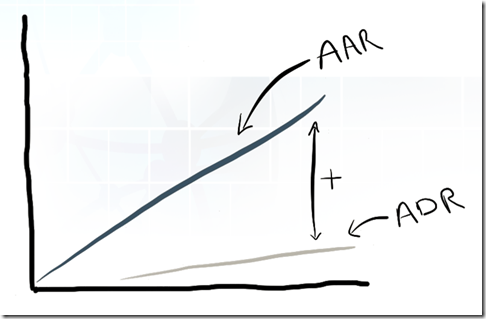

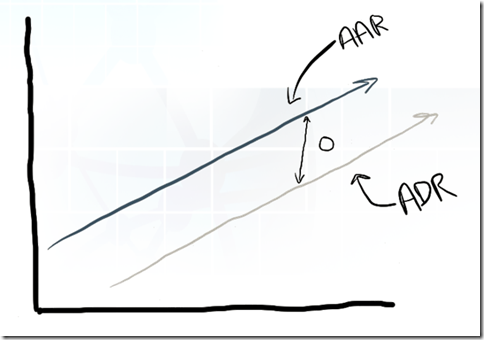

With even just a couple weeks of data that visualizes how work moves through our system, we can now start measuring Average Arrival Rate (AAR) and Average Departure Rate (ADR) between any two states in our system. AAR and ADR are simply represented as the slope of a line. If we calculate the rise (x-axis) over the run (y-axis) values, we get the slope.

It is the relationship between the two values that is interesting to us and will allow us to more empirically set the WIP Limit values in the system. Based on our understanding of Little’s Law, we are striving for a average rate of divergence between the two of near 0.

A negative divergence suggests the WIP limit is to low and that we are under utilized.

A positive divergence rate suggests the WIP is too high and we are overburdened.

Since ADR (the rate at which we finish work) represents our current capability, the value of ADR should be considered a great candidate for the WIP limit for this state. With the the right WIP limit in place, AAR should match ADR and we will find an average divergence rate of 0. As your team’s capability changes, our divergence will go either positive or negative and will provide an indication of when our WIP limits should change and what they should change to.

And there you have it! When the rate of divergence between AAR and ADR is near zero, we know that our WIP limit is right and that we’re satisfying one of the assumptions required to make Little’s Law work for us!